The Violence Against People Behind Bars That We Don’t See

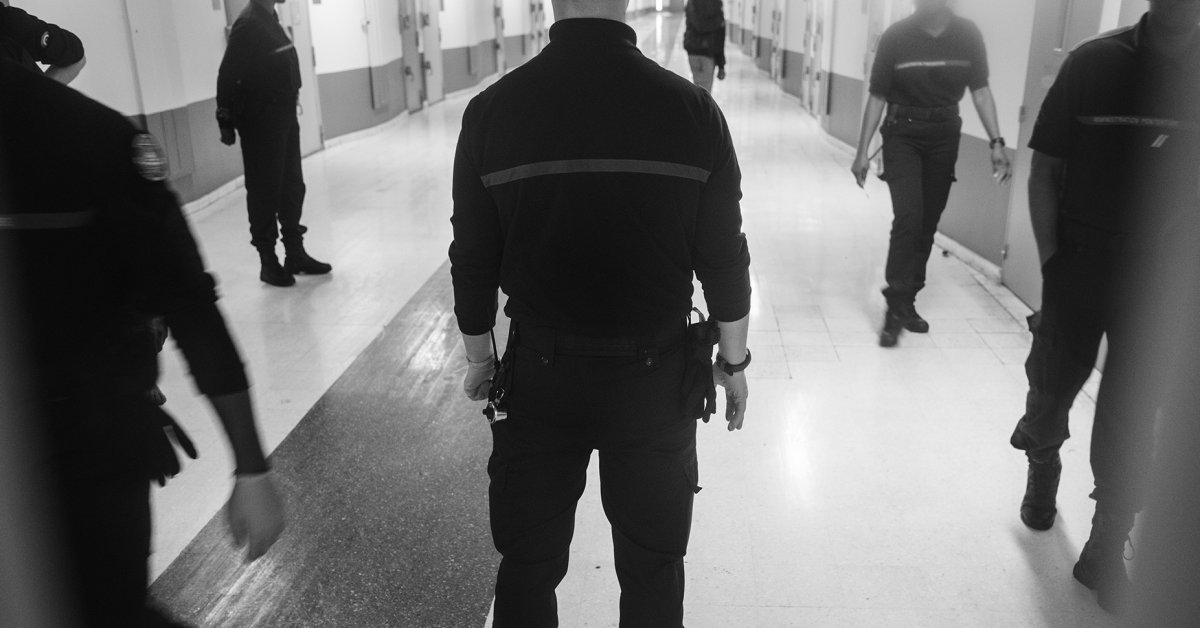

The constant violence perpetrated by police officers on Black and Latino people can now be seen by the broader public, thanks to cellphone videos and police bodycam footage. But what we almost never see is the regular abuse people behind bars endure at the hands of correctional officers.

The use of excessive force against prisoners, from punches to chemical spraying, is an everyday occurrence that violates our constitution. Taking measures like installing more cameras to hold perpetrators accountable and implementing meaningful oversight of our nation’s prisons are important to curb abhorrent conditions of confinement. But we need to also prioritize taking steps to significantly reduce mass incarceration so that we are no longer the world’s number one incarcerator.

The late Columbia Law School professor Robert A. Ferguson put it best: we have created a criminal justice system that is divided so that, post-conviction, the “suffering of the convicted is carefully arranged to take place somewhere out of sight.”

In a recent report, the Justice Department and Alabama’s three U.S. attorneys exposed what happens behind the prison gates in their state. They found pervasive use of excessive force against those incarcerated in men’s prisons, identifying violations of excessive force rules in 12 of the 13 Alabama prisons reviewed. Correctional officers, the report said, often relied on force “while making no effort to de-escalate tense situations.”

It took years of officials visiting these prisons, interviewing those who worked and were imprisoned there, speaking to family members of those who were incarcerated, and analyzing reams of testimony, documents, emails, videos, medical records, and more to understand how those who were under the supervision of the state of Alabama were deprived of not only their constitutional rights, but of their humanity.

In one incident, a prisoner stuck his tongue out at a sergeant. The sergeant responded by punching the handcuffed prisoner in the face. The report also found that Alabama’s correctional officers frequently use chemical spray on prisoners while they remained in locked cells.

Although this report was not focused on racial disparities, it’s important to acknowledge who comprises Alabama’s male prisons. Currently, Black men represent 50% of Alabama’s overall prison population and 55% of its male prison population. Yet, only 26.6% of Alabama’s overall population is Black.

The Justice Department’s recommendations for how to remedy Alabama’s constitutional violations range from installing more cameras to allowing prisoners to register formal complaints about uses of force. It is shocking that some of the recommendations aren’t already status quo. But cases of violent staff and a lack of accountability are commonplace beyond Alabama in our country’s vast network of jails, prisons, and detention centers. A group of formerly incarcerated women from New Jersey recently testified they were sexually assaulted and harassed by corrections officers who came into their cells at night while security cameras were pointed at ceilings. In 2018, the Intercept published data uncovering that 1,224 instances of sexual assault were reported in ICE detention centers and only 43 complaints were investigated.

These problems can’t be fixed overnight, yet improvements like some of the DOJ’s recommendations are within reach. In addition, and most importantly, we need to meaningfully reduce our prison population.

Research from the Brennan Center for Justice shows that in 2016, nearly 40 percent of the U.S. prison population — 576,000 people — were behind bars for no compelling public safety reason. Our analysis found that 25% of those in state and federal prison—364,000 people—most of them convicted of less serious crimes, would be better served by off ramps from the justice system such as diversion and programming, without spending even a day in prison. We also found that about 14% (212,000 prisoners) had already served long sentences for serious crimes and could be safely released. Considering we would need to cut our incarceration rate by approximately 75 percent just to line up with the average of the rest of the world, we could start there.

In states like Alabama, with an extensive backlog of parole-eligible cases, releasing people who are eligible for parole is another key way to remove them from a harmful prison setting. Alabama should also create an independent oversight entity with the authority to conduct surprise inspections of prison facilities and check on those who are incarcerated.

In January, a task force created by Alabama Governor Kay Ivey to study the state’s prison system recommended a broad array of solutions to improving Alabama’s prisons, including increasing funding to hire additional correctional staff, expanding medical and mental-health services, and adding educational programs. The task force also called for implementing early release incentives for those who complete certain programs.

But the governor’s recommendations will fall short without a serious culture shift within our prisons and a true, national de-carceration effort. Incidents of sexual assault and violence are far too common in our nation’s prisons and jails. More than 95% of those in our prisons will eventually leave and reintegrate into their communities. We must greatly reduce our use of incarceration, or we condemn people not only to time away from their families and communities but also to years of abuse.

tinyurlis.gdu.nuclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.detny.im