How the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Cancer Care, In 4 Charts

Before the pandemic, about 1,000 new patients came to Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for treatment consultations each week. When COVID-19 hit Massachusetts this spring, the number of new consultations fell by half and the hospital moved as many appointments as possible online.

Now, with daily case counts relatively low in the area, the hospital is back to scheduling about 800 consultations per week, using a mixture of telemedicine and in-person appointments, says associate chief medical officer Dr. Andrew Wagner—but that still means about 200 cancer patients per week are not getting the treatment consultations they would in more normal times. Continued travel restrictions and fear of infection likely play a part, but many would-be patients aren’t setting up appointments because they don’t know they need to. The number of cancer screenings happening nationwide plummeted this spring when lockdowns went into effect, meaning many of the people who would be seeking care from Wagner and his colleagues don’t yet know they have cancer at all.

“Five months in, with the procedures and equipment we have put in place to ensure the safety of our patients and our staff, the potential health impact from [canceling cancer screenings] is a bigger concern than the pandemic,” Wagner says.

When COVID-19 hit the U.S. this spring, hospitals in many areas canceled elective surgeries to redirect resources and personnel to treating coronavirus patients, and people were encouraged to use telemedicine or delay non-urgent medical appointments. While doing so was necessary to try to stop the spread of the virus, it led to unintended consequences. About 40% of Americans recently said they were unable to get some kind of care due to the pandemic, and studies show emergency room visits plunged nationwide.

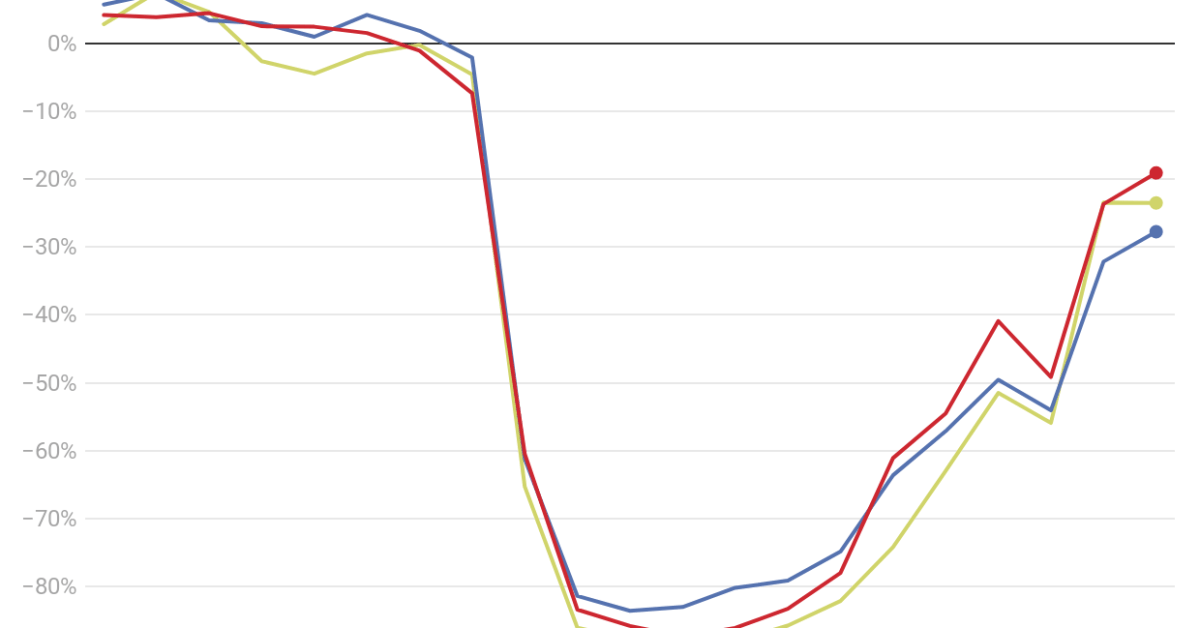

For cancer patients, the unintended consequences start with those who don’t even know they have the disease yet. Studies suggest the pandemic led to a roughly 80% drop in routine screening appointments that could catch new cancers in March and April. Rates recovered somewhat in the late spring, but one paper still estimated approximately 60% fewer breast, colon and cervical cancer exams from mid-March to mid-June compared with years prior. That translates to hundreds of thousands of missed exams nationally—and, among those who do have undetected cancer or precursors to it, the loss of potential early diagnoses and interventions.

Part of the problem, Wagner says, is that the vast majority of cancer screenings can’t happen virtually. Most screenings require an in-person procedure like a colonoscopy (for colon cancer), mammogram (for breast cancer) or a pap smear (for cervical cancer). Some clinics can test for colon cancer with a stool sample patients send in from home, and dermatologists may be able to look at an unusual mole remotely—but that’s about where the list ends.

Even remote tests for colorectal cancer aren’t used as often as they could be, says Dr. Rachel Issaka, a gastroenterologist and clinical researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. “In this era of social distancing, this really is an opportunity for us to start to use these tests to a greater extent,” Issaka says. “This time is requiring us to be a little bit more creative.”

The stakes are high. Fewer screenings translated to fewer cancer diagnoses during the pandemic, data show. According to one estimate, the number of weekly diagnoses for breast, colorectal, lung, pancreatic, gastric and esophageal cancers dropped by about half during the pandemic.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force sets specific recommendations for who needs which screening tests, and how often. Most cancers are slow-growing enough that missing those intervals by a few months won’t make a huge difference, says Dr. David Cohn, chief medical officer at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. “But the biggest fear is that a couple months turns into a couple years,” he says. If a cancer goes undetected for years, the patient’s prognosis could be grim, he says.

Patients who had been diagnosed prior to the pandemic have experienced disruptions, as well. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention never recommended that people with a cancer diagnosis delay their care, but cancer patients and their doctors have had the difficult task of weighing the risk of COVID-19 against the urgency of cancer treatment. As TIME reported last month, some patients have deferred chemotherapies and radiation treatments that need to be administered at medical facilities under professional supervision.

In one April survey of breast cancer patients, 44% reported treatment delays during the pandemic—a number that was relatively steady regardless of the stage of cancer. The highest rate of delays concerned routine follow-ups and breast reconstruction surgery. But about a third of respondents reported delays in cancer therapies that take place in a medical facility, including radiation, infusion therapies and surgical tumor removal.

It’s too soon to say what the fallout from all the delays in screenings, diagnoses and treatments will be. Dr. Ned Sharpless, who leads the National Cancer Institute, which is part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, estimated that pandemic-related delays in screenings and cancer care will over the next decade result in about 10,000 excess deaths (on top of the 1 million typically expected deaths) from breast and colorectal cancer alone. The analysis of these two cancers, which account for about a sixth of all cancer deaths, is based on a conservative model that assumes pandemic-related delays last only six months.

“Even a small dropoff has a very substantial impact on population health,” Cohn says.

We won’t see these deaths show up in the data for a few years, since many cancers progress in severity over a relatively long period of time.

Most hospitals and doctors’ offices are again encouraging patients to come in for routine care. Many have implemented safety protocols (like limitations on visitors, getting rid of waiting rooms and mandatory COVID-19 testing for certain patients and staff) that make it safe for most patients to come in for screening tests, Cohn says.

And there is at least one way telemedicine can help cancer care, Cohn says. Patients who are nervous, or who have unique risk factors, can talk through the risks and benefits of making an appointment with their doctor first, from home.

tinyurlis.gdclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de